Poetry Pamphlet - Ten Minutes of Weather Away

Ten Minutes of Weather Away will be launched online, along with Patricia Helen Wooldridge’s pamphlet, Being, on April 15th at 7.30pm.

If you would like to join us you can register online for the Zoom webinar using this link.

"This pamphlet is wonderful, utterly oozing with passion for the earth, sensuous, moving, delightful. And all those tree poems! I'll be reading it over and over."

~ Mandy Haggith

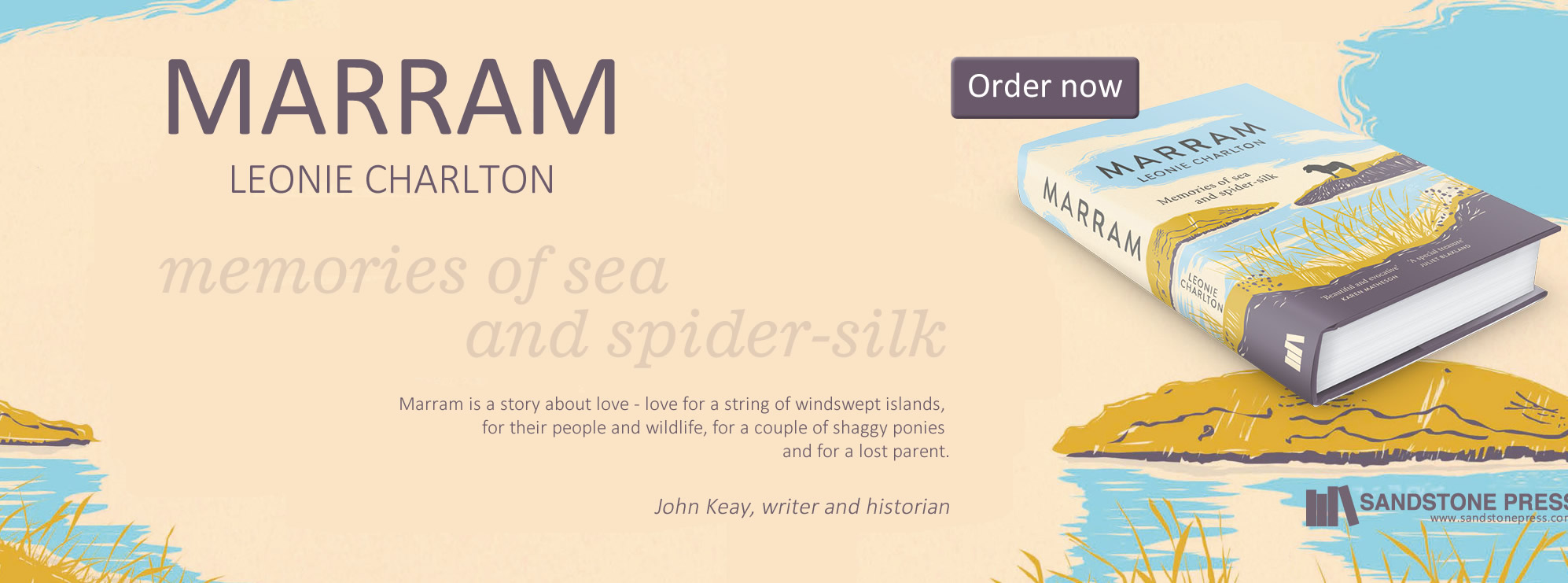

MARRAM

Memories of sea and spider-silk

Publisher: Sandstone Press Ltd

ISBN: 9781913207106

Number of pages: 256

Dimensions: 198 x 129 mm

Review of Leonie Charlton’s, ‘Marram’

––by Ali Whitelock

When people ask Leonie where she is from, ‘no, where are you really from?’, it is clear on reading ‘Marram’, exactly where that place is.

This is a story of grief, of landscape, of friendship, of ponies. To say that ‘Marram’ is beautiful, is not enough. It is a work of art––tender yet profound, a deep meditation not only through the islands of Barra, Benbecula, Harris and Lewis but also through grief––written with a poet's eye and a poet's heart. What a journey Leonie take us on––through ‘aubergine’ hills, past 'roofs of peacock green and teal blue', irises a 'dense yellow', lichen a ‘deep tourmaline'. Leonie paints the extraordinary beauty of these islands while delicately weaving profound memories of her mother and her relationship with her, into the hills, the sea, the marram and the machair.

Apart from the striking visual beauty, there is the sensory; the strong coffee on the camp stove I can almost smell bubbling away, the pungency of the canned sardines I can almost taste, the piquancy of tabasco sauce, crumbly oatcakes, dark chocolate, the clatter of washing pots and pans in the sea.

As a Scot living in Australia, I feel a much missed nip in the Scottish air as I read,

‘The tent was up … we put more wood on the fire … I picked up the half bottle of Jura Superstition and poured another peaty dram. The north-westerly breeze lifted ash and smoke from the fire. Gulls called as they fed off the sea coming in over the warm sand.’

Leonie’s relationship with her mother was difficult. Leonie takes a purse of her mother’s precious beads on the journey with her, intent on leaving each bead in carefully chosen spots in the landscape, a way of laying to rest the past and we are privy to the heart wrenching conversation she has with herself about her regrets,

‘I wish I’d gone in for cups of tea, I wish I’d taken her to eat mussels on the pier in Oban that sunny April day, I wish I’d gone in to talk to the surgeon with her, …’

The nuances of Leonie’s grief reveals itself here as she walks through a graveyard on Harris, stopping by a shiny granite stone,

‘… erected for Angus MacLeod who died at Quidinish, 20th March 1915 by his sorrowing widow.’

Leonie goes on to ponder the word, ‘’Sorrowing’. Noting,

‘How much rounder and fuller it was than the word ‘grieving’’.

This single line shows us that grief is never linear but round and full––almost three dimensional.

As the journey moves on we are introduced to a vast array of birds––skylarks, oystercatchers, corncrakes. Leonie’s love of birds and nature and wildlife is palpable. The tenderness with which she refers to each species, each blade of grass, each tiny flower is careful, precise, tender and poetic.

Leonie and Shuna meet such kindness and generosity throughout the islands––the ponies are welcomed with fields and troughs of fresh water, and are never far from an exhilarating canter on these exquisite island beaches. Locals open up their crofts, offer a meal, a bed, a cup of tea, a hot shower. Highland hospitality is world renowned. Even if we haven’t been to the Highlands ourselves, it’s what we’d all hope to receive from the locals there.

Memories of the lead up to Leonie’s mother’s death and her death itself fall gently throughout this prose like soft mist,

‘I remembered the cold day my brothers and I took Mum’s ashes up to the top of Deadh Choimhead … I remembered the wind that day, how it had blown her ashes back against us, into our eyes, our hair, our mouths.’

As the journey moves from Barra and all the way to Lewis, the book tracks the subtlety and yet the enormity of how Leonie’s relationship (or memory of her relationship) with her mother changes as her travels progress. Her growth, her emergence into a new light are evident in this beautiful sequence,

‘... my head emptied into the banks of the burns, between peat hags, across the stony surface of the hilltops. That would have been the place to have left a bead for her, on that lunar ridge, but I hadn't. Instead I'd left a part of Beady, a part of myself that I no longer needed.'

As the journey nears its end, Leonie is missing her children––wanting to be back home with them,

‘I reached into my pocket for the bead purse and took out three, one for each of my children ... I threaded them together onto a single string, I didn't want them to become separated.’

When I finished reading the final page in 'Marram'––my heart was in my mouth, and never have I been happier to read of hooves and feet no longer in soft peat but back on hard track in Callanish. The ordeal experienced at Kiloch Reasort was terrifying, that terror and horror so beautifully told.

Leonie’s emotional journey starts to come to a close with this,

‘Let Mum, the woman who taught me to believe in Faeries, just be a part of me now. Let that be enough.'

As I closed the cover on my copy of ‘Marram’, I poured myself a peaty dram and raised my glass not only to Leonie, Shuna, Ross and Chief, but to the aching beauty of these islands, to nature, to friendship, to courage, to grief and to sorrowing.

––Ali Whitelock, April 2020.

Author of:

'the lactic acid in the calves of your despair'

'and my heart crumples like a coke can'

'poking seaweed with a stick & running away from the smell'